This is from 538, here, citing TheDemands.org:

The most common demands, according to our analysis, have been for schools to increase the diversity of professors, offer sensitivity training to students and faculty members, and create or expand support for cultural centers on campus. The demands at more than a quarter of these schools (14) included a deadline by which school administrators needed to agree or respond, or else face escalations of protests.

Federal law limits the means the university can use to address the demands regarding increased diversity. For example, the SCOTUS will hear the Fischer v. University of Texas case on racial preferences in college admissions on Dec 9th, though the decision presumably won’t come until June. The NYT has a lengthy discussion, here:

The United States Supreme Court will hear arguments on Dec. 9 in Fisher v. University of Texas, a case challenging affirmative action in university admissions. Emily Bazelon, a staff writer for the magazine, and Adam Liptak, The Times’s Supreme Court correspondent, have been exchanging emails about the possible outcomes of the case and what they might mean at a moment of debate over race in American higher education.

Adam,

It’s been a season of attention to racial inequality on American college campuses. Across the country, sometimes eloquently and sometimes not (these are 18-to-22-year-olds), minority students and their supporters have channeled the spirit of Black Lives Matter and demanded more. More black and Hispanic and Asian and Native American faculty members. More resources. A greater sense of belonging.

The Supreme Court may be poised to make them settle for less, in the most basic form: fewer seats in the future entering college and university classes.

The justices will hear arguments on Wednesday in Fisher v. University of Texas, a case that challenges the consideration that the University of Texas, Austin, gives to race in admission. This is the second time the court has heard the claims of Abigail Fisher, a white woman who didn’t get into U.T. Austin seven years ago. The university says Fisher wouldn’t have gotten in even if race had played no role in the decision, because her other qualifications were lacking. Nonetheless, the justices let her case proceed, and now they’ve brought it back for a second round. That is not a good sign for supporters of affirmative action. …

On the faculty hiring front, UO has a “Underrepresented Minority Recruitment Plan” that gives $90K to departments that hire a minority faculty. At one point minority faculty could and did use these funds for course buyouts and summer salary. However, after a DoE Office of Civil Rights investigation UO General Counsel Melinda Grier agreed to adopt new rules specifying that the funds go to the department not the hire, and requiring that any benefits paid from these funds not be based on race or ethnicity. So if your department hires a new minority professor the department gets $90K, which they can use to give summer salary for *all* new hires.

On the student front, UO used to offer minority-only sections of math classes. Those were shut down as part of a consent agreement with the OCR, after a non-minority student complained. (We’ve started offering these sections again, but entrance is apparently not restricted to minorities.)

Interestingly, while federal law is pretty strict about not giving benefits to people based on race, ethnicity, or gender, there is pretty much nothing that prevents giving preferences to low income students or first generation students. Not that I’m a law professor.

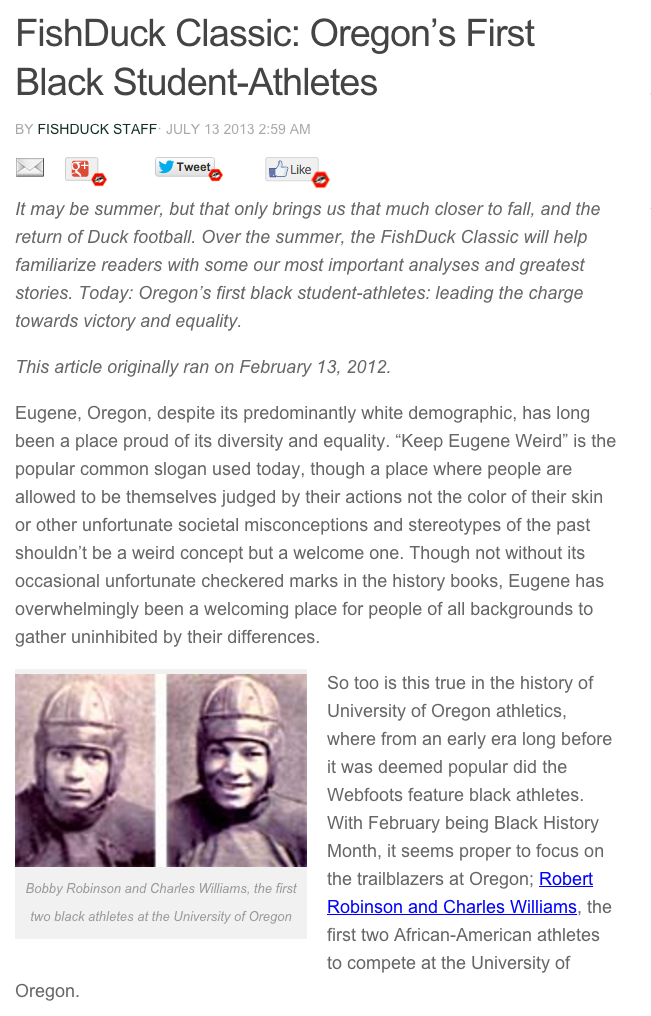

Last, here’s a bit of history about the important role that black football players had in the integration of UO:

It was not without its difficulties though, as both Robinson and Williams were initially barred from living in campus dorms, having to find housing in off-campus apartments during their freshman year. Their white teammates signed a petition and submitted it to the school under protest demanding that their fellow players be allowed to live on campus in the dormitories alongside their peers. By their sophomore year the university relented, allowing Robinson and Williams to reside in Friendly Hall, albeit separated from others and permitted to enter the building only through their own designated entrance. On road trips too they were segregated from the rest of the team, not permitted to stay in the team hotel, though Williams later confirmed that despite the separate living quarters both managed to mingle with their fellow students and teammates just fine. Often on road trips after check-in at a hotel their white teammates would sneak them into the hotel anyway to stay with the rest of their fellow Webfoots.

Read it all, here:

“Many of these demands are limited by federal law.”

“Many of”? I don’t see that at all. For a couple of the demands, specifically related to increasing faculty and student diversity, there are limitations to the means that universities can use – but the goals themselves are not illegal. Moreover, that’s only a couple of them. Most of the demands concern things that are uncontroversially within universities’ control – things like requiring certain educational experiences (which all universities do as a fundamental part of their existence), providing student services, tracking crimes better, etc.

You can certainly debate the merits of some of these demands. A university can say “sorry, we have decided we are not going to do that” to any or all of them. But saying “sorry, the federal government won’t allow us to do that” would be untrue.

Good point, I’ve corrected the post.