Last updated on 03/12/2018

2/7/2018: From The Times:

All seven of the UK’s research councils have signed up to a declaration that calls for the academic community to stop using journal impact factors as a proxy for the quality of scholarship.

The councils, which together fund about £3 billion of research each year, are among the latest to sign the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment, known as Dora.

Stephen Curry, the chair of the Dora steering committee, said that the backing of the research councils gives the initiative a “significant boost”.

Dora was initiated at the annual meeting of the American Society for Cell Biology in 2012 and launched the following year. It calls on researchers, universities, journal editors, publishers and funders to improve the ways they evaluate research.

It says that the academic community should not use the impact factor of journals that publish research as a surrogate for quality in hiring, promotion or funding decisions. The impact factor ranks journals according to the average number of citations that their articles receive over a set period of time, usually two years.

Professor Curry, professor of structural biology at Imperial College London, announces the new signatories to the declaration in a column published in Nature on 8 February. …

1/26/2018: Nobel laureate unimpressed by VP Brad Shelton’s shiny new metrics plan

The 2016 Nobel Prize for Economics went to Oliver Hart and Bengt Holmstrom, for their life work on optimal incentive contracts under incomplete information. Holmstrom started out in industry, designing incentive schemes that used data driven metrics and strong incentives to “bring the market inside the firm”. However, as he said in his Nobel Prize lecture:

Today, I know better. As I will try to explain, one of the main lessons from working on incentive problems for 25 years is, that within firms, high-powered financial incentives can be very dysfunctional and attempts to bring the market inside the firm are generally misguided. Typically, it is best to avoid high-powered incentives and sometimes not use pay-for-performance at all.

I thought that Executive Vice Provost of Academic Operations Brad Shelton and the UO administration had learned this lesson too, after the meltdown of the market-based “Responsibility Centered Management” budget model that Shelton ran. Apparently not. Today the Eugene Weekly has an article by Morgan Theophil on “Questionably measuring success” which focuses on UO’s $100K per year contract with Academic Analytics for their measure of faculty research “productivity”.

Brad Shelton, UO executive vice provost of academic operations, says Academic Analytics measures faculty productivity by considering several factors: How many research papers has this faculty member published, where were the papers published, how many times have the papers been cited, and so on.

“Those are a set of metrics that very accurately measures the productivity of a math professor, for example,” Shelton says.

No they don’t. They might accurately count a few things, but those things are not accurate or complete measures of a professor’s productivity, and as Holmstrom explains later in his address – in careful mathematics and with examples such as the recent Wells Fargo case – there are many pitfalls to incentivising inaccurate, incomplete, and easily-gamed metrics. Most obviously, incentivizing the easily measured part of productivity raises the opportunity cost to employees (faculty) of the work that produces the things that the firm (university) actually cares about it, so true productivity may actually fall.

As the EW article also explains, UO has spent $500K on the Academic Analytics data on faculty “productivity” (i.e. grants, pubs, and citations) over the past 5 years, prompted in part by pressure from former Interim President Bob Berdahl, who now has a part-time job with Academic Analytics as a salesman.

Despite this expenditure, UO has never used the data for decisions about merit and promotion, in part because of opposition from the faculty and the faculty union, and in part because of a study by Spike Gildea from Linguistics documenting problems with the accuracy of the AA data. And today the Chronicle has a report on the vote by the faculty at UT-Austin to join Rutgers and Georgetown in opposing use of AA’s simple-minded metrics.

Meanwhile back at UO, VP Shelton is trumpeting the fact that AA has been responsive to complaints about past data quality:

“What we found is that Academic Analytics data is very accurate — it’s always accurate. If there are small errors, they fix them right away,” Shelton says.

Always accurate at measuring what?

Word from the CAS faculty heads meeting yesterday is that UO will not require departments to use the AA data – but that we’ll keep paying $100K, or about the salary of one scarce professor for it. Why? Because some people in Johnson Hall don’t understand another basic economic principle. When you’re in a hole, stop digging:

I forget who got the Nobel Prize for that one.

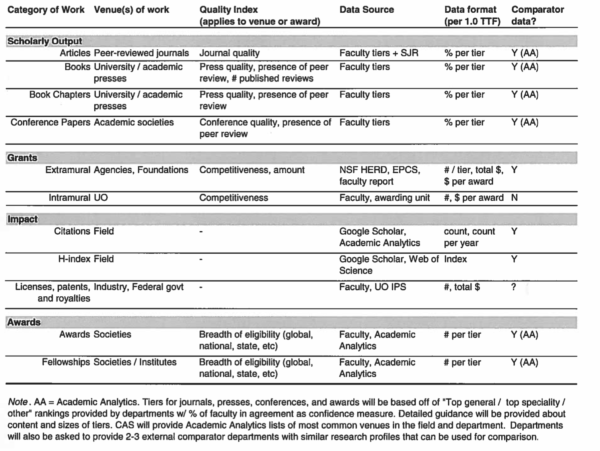

Here’s a draft of the sort of departmental incentive policies that are now floating around, in response to Shelton’s call:

Keep in mind that even if your department decides to develop a more rational evaluation system for itself, there will be nothing to prevent the Executive Vice Provost of Academic Operations from using the Academic Analytics data to run its own parallel evaluation system.

Shouldn’t deans already know which departments (and in many cases, individuals) are doing good work and which ones aren’t? Isn’t this their job?

My prediction: We’ll spend a lot of money and faculty time on this. The metrics produced will not be reliable for comparing departments across campus or between comparator schools. The initiative will lose the confidence first of the faculty (if there ever is significant faculty buy-in in the first place) and then of administrators, but will limp along as something that department heads will have to keep up-to-date in spite of its uselessness.

I think the deans fully know who he doing good work and more

specifically who is not doing this good work. However, I think their metric is anything but objective but mostly judgmental and often

prejudicial.

http://stochastictrend.blogspot.ca/2018/01/how-to-count-citations-if-you-must.html

citation metrics are useless ACROSS between subdisciplines; consider economics, like the above

Thanks, Econ prof. always good to have an economist to give a clear explanation.

yeah I would be happy if the UO gave me $10 for each one

of my citations discovered by AA …

Sad that Brad Shelton, who used to be a good colleague and a decent mathematician, is falling for this dreck.

I am reminded of the old nostrum: “Those who can, do; those who can’t, go into administration.”

My guess, though I have no real knowledge here, is that the push for metrics is coming from higher up than Brad.

There are significant mathematical (and social and political) obstructions to identifying, collecting and using metrics for the purposes of comparing departments and faculty, and I think Brad (and others) in Johnson Hall know this.

Instead of spending tons of faculty (and administrator) time trying to build a unicorn, someone who understands the obstructions and who is listened by these higher-ups (Brad) needs to just come out and say ‘unicorns don’t exist, I can get you a horse, but you’ll still need to use your judgement on when and how to ride it’.

I agree, it is probably coming from Banavar, and/or Schill, and/or Lillis and the UO board. Still, Brad is responsible for what he says, even if he is only channeling them.

wouldn’t it be something to learn from evidence and experience?

from Theophil’s article:

According to the AAUP, Rutgers University signed a $492,500 four-year contract with Academic Analytics in 2013. By 2015, the school disregarded all use of the data, saying they “hardly capture the range and quality of scholarly inquiry, while utterly ignoring the teaching, service, and civic engagement that faculty perform,” and “the Academic Analytics database frequently undercount, overcount, or otherwise misrepresent the achievements of individual scholars.”

isn’t “’teaching, service, and civic engagement’” the kinda thing the CAS vision statement is all about? and the kinda thing that dominates the life of us “Nons” (NTTF)? No wonder NTTF aren’t mentioned anywhere in the grand Vision. Can’t wait to see if they try to fit us into all this metrics malarkey.

Thanks for posting this article, UOM! As one of the people involved in creating the metrics worksheet posted above, let me say we’re all well aware of the limitations of AA data and the risks inherent to metrics (even accurate ones!). So I’d like to add a couple of things to this discussion:

– One of our goals here is actually to _move away_ from AA by gathering our own data based on the performance areas we care about. We evaluate ourselves all the time; this is an opportunity to think about what implicit criteria we’re using when we think about a department and make those criteria explicit.

– We will soon be asking departments for input. That is because faculty within departments are far more knowledgeable about what good scholarship looks like in their fields. If you have ideas of ways to measure scholarly/creative activity beyond what is listed there, we’d love to hear them. Again, the goal is to articulate what specifically we’re thinking about when we think about quality in our fields.

– As Chris noted, the deans already know quite a bit about the quality of departments. By examining the parts of faculty output that can be quantified, we can provide a multifaceted and transparent (if incomplete) check on that knowledge. Making the criteria for quality explicit and transparent can reduce some of the biases that come along with summary evaluations of departments.

– The worksheet above is limited only to scholarly and creative output. Teaching and service are not forgotten but rather will be addressed separately. (Actually, my sense is that scholarly and creative output is actually easier to quantify than teaching and service.)

– The metrics are meant to serve alongside contextualizing information (e.g., narrative evaluations by deans, faculty, and others) to provide a more complete snapshot of a department. We are keenly aware that quantitative data alone are almost always uninterpretable.

– By developing our own set of metrics instead of AA, we’ll be able to update them far more frequently as fields evolve (e.g., as new subdisciplines emerge along with their own presses and journals).

– Incentives will not be tied directly to these metrics (in contrast to the cases studied by Holmstrom). Instead, they will be a way to make transparent and explicit the information that we think we glean when, say, we scan a CV. P&T decisions haven’t been decided based on a review of someone’s CV, and they still won’t. But this process will ensure that two people who have comparable CVs – but who might be different in other ways irrelevant to performance – will wind up with the quantitative score on that piece of the evaluation.

In an abstract sense, what these metrics are trying to capture is a grade (or grades) for departments. This is a reasonable goal, especially since we are in a resource constrained environment.

It is clear that these departmental grades cannot be assessed by the same criteria across campus or even within colleges.

Using grades based on different assessment criteria as a basis for comparison seems ridiculous to me.

Student X gets a B- in Math 111. Student Y gets an B+ in Art History 201. Which is the smarter student?

I don’t think department grades are very useful information for improving the university. Prospective students or faculty probably want that information, but our goal is to improve our university, not choose between universities.

What would be useful would be a forecast of the impact on our excellence goals from redirecting resources from one department to another. No one in JH has yet explained to me how these retrospective metrics will be useful for that purpose. I’ve asked that question in meetings, as have others including Elliot, and the answers have been along the lines of “Good question, we hadn’t thought about that.” Really.

So think about it: Department A has a three-year rolling average of 4 pubs per professor per year. Dept B has 3 pubs per prof/year. To make it easier, assume the departments are identical on every other measurable dimension. Now assume that UO has the money to hire one new professor. Does the 3 vs 4 info inform your decision to give it to A or B, and if so how?

But it’s easy to see how they will be misused as incentives. If your department boosts pubs by 10% etc., you might get another faculty line a few years later. Faculty will respond to these incentives by shifting their efforts from high quality research, mentoring, good teaching, service, and all the other important things that can’t be easily measured towards those few and generally less important things that can be measured.

We’ll be a worse university but life will be sweet for our administration, who won’t have to work as hard making decisions or explaining them. They’ll just use the AA metrics and the eDean app. (TM)

yeah all of these points are valid but know want 50$ per citation as I know my citations have more IMPACT than those for Economic prof.

My department’s button is bigger that your departments button …

I know a guy in my department who says he can easily crank out a paper a month. It is because of the nature of his work. I know someone else who works full-time, with graduate students, and probably puts out 2-3 papers per year. Whose is the research that I value more highly? The second one, because it is more interesting, and requires much more thought and effort. “Counting pubs” is a silly way to measure research “productivity.” I’m told by someone in Physics that Einstein in his “annus mirabilis” published 4 papers. At UO, in some departments, he would now be considered a loser! If academia has come to this, evaluating research by pure bean-pounting “metrics,” then things have gone completely haywire.

Oh come on … “if academia has come to this …” – what do you mean … its been like this for some time, but most people deny this. We have no way of properly evaluating the integrated scholarship of research, teaching ,service, outreach, etc – we just pretend that we do.

“Counting Pubs” ( and weighting them by presumed impact in your field) is what we do primarily. Now, this does properly identify faculty that are below some average in this coin of the realm, and that is useful – but the converse is not true, it does not separate out “excellent” faculty from those that simply maintain a productive research profile, like they are supposed to do as part of their job.

In my experience, most of us are considered “losers” by someone else’s measure.

dog, you know that I always try to give the benefit of the doubt. It has certainly been evident for some how the wind is blowing. But it has only recently become overt and official.

Maybe it has become harder to see things in the old ways because increasingly the emperor has no clothes? I think for example of economics. (Sorry Bill!) Despite probably hundreds of thousands of papers, it’s hard to say that there’s been much real progress over the past 40 years or so.

in general dogs don’t know shit

however, my observation has been that, fairly consistently,

what happens on the ground at the UO is often quite different

than what our policies are. I have seen this play out in person

more than a few, disgusting, times.

These are good points, and I can say this is exactly the kinds of issues that have been raised often in meetings about metrics. A few related points:

– Cross-department comparisons are extremely tricky – we all know this. A more realistic goal is to start gathering data and monitoring year-over-year trends within departments. For example, did faculty in my department (adjusted for total FTE) publish more, fewer, or about the same papers in this biennium than last? Same for grant proposals? It will be non-trivial to interpret the results in any case, but right now we don’t even have an easy way to answer those questions.

– Some of this discussion is focusing exclusively on publication count, which is just one metric under consideration. Another one is citations. Citation count at least indirectly implies an assessment from others in the field (assuming the bulk of it does not come from self-citations). An interesting exercise: take a look at your own publications and score them on “quality,” whatever that means to you. Then look at citations for each, and compute a correlation. Personally, some of my most cited papers are meh, and some of my least are what I consider to be some of my best work. But, for the most part, there is a positive correlation there. It does not strike me as controversial to say that citation count is a rough index of quality and/or impact. Now, aggregate that across an entire department, and there is probably some meaningful signal.

– I am not yet ready to throw my hands up and say that scholarship quality is immeasurable. That seems unscientific. If we believe that quality exists, even if it is multifaceted, which it surely is, then there is probably some way or ways of measuring it. A productive direction for this discussion would be to consider what that might look like.

– In some ways, having data on hand will make Dean/Provost/Pres decisions harder because the information that feeds into those decisions will be more transparent. We can all watch the data and see how decisions do (or do not) correspond to them. Decisions will still need to be justified.

[as always, the opinions I post here do not necessarily reflect those of my lab or department]

Let me try the question a little differently Elliot.

Department A has a three-year rolling average of 40 cites per professor per year. Dept B has 30 cites per prof/year. To make it easier, assume the departments are identical on every other measurable dimension. Now assume that UO has the money to hire one new professor, Does the retrospective 30 vs 40 info inform your decision to give the line to dept A or dept B, and if so how?

Mainly on Elliot’s penultimate point here. Thank you for engaging in debate here – very helpful to hear the view from inside the engine room. But: it is unscientific to insist that something obviously beyond the realm of discrete measurement must nevertheless be so measured. The term “unscientific” is being rhetorically skewed by management-speak to mean “poorly reasoned”, with a hint of a silencing “that’s not the way you’re supposed to think”. On the contrary, if you’re serious about “what it might look like”, you’re going to have to accept that it will be very, very subjective, and be based on things like assessors’ taste and expertise, candidate’s reputation (not citations, but what people think and say), networking etc. There are areas in which statistical checks and balances can help correct for biases within what is still a rather monolithic profession, above all in terms of diversity, but that’s not at all the same as measuring quality. As for “citation count is a rough index of quality and/or impact”, really? I mean, really? Just for a start, why do you dismiss your own experience so readily? I can understand how, as an administrator, one might use this as a convenient fiction to keep the job simple (Bill’s iDean app), but it’s a bit unnerving to hear you trot it out so innocently in a forum such as this.

The central problem, from my limited perspective, is that there is no agreed upon total or partial ordering of researchers/departments. (Moreover, if I understand Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem correctly– which I probably don’t–there can’t be). Thus, any measurement we use to quantify research productivity (or whatever) will lead to comparisons that are not universally agreed upon.

This seems like a pretty significant mathematical obstruction.

Even if there was some god-given partial ordering of researchers (or departments), it would be a very hard problem to identify a metric which captured the ordering. If there is no god-given ordering then the search for such a metric is folly.

Now I have lost track about what any of this is about:

a) why does their need to be ordering>

b) by whatever metric do we reward strong departments

with more faculty lines (which would weaken them – it has

in the case of my own department)

c) do we “eliminate” weak departments (and are they weak

because of topical area or faculty?)

d) Is this all done in the name of let’s develop a metric, if followed, will make us more “excellent” in terms of that

metric. This is a circular argument (possibly the Theorem of

the Arrow) and no such metric exists.

e) so what the hell is going on?

Thanks for the responses. Here are my hot takes on the points in order:

UOM: Your example illustrates a couple of things. One is that it underscores how important human judgment will remain in the decision. In an ideal world, our leadership would have as much information as possible – both holistic, contextual information AND discrete, quantitative data – to make decisions. Part of the attempt here is to find quantitative data to complement, not replace, what is already known. The second is the importance of comparator data (note: we are still a long way from this point). What any decision-maker should want to know in your case is what the mean # cites / prof / year of comparable departments to Departments A and B, plus the field-level trends over time. Again, we are a long way away from having any of that, and have made no serious attempt to even try to get it.

Heraclitus: I think you’re being ungenerous with my use of the term unscientific. I was looking for a word for believing that a psychological construct exists along a continuous scale but is immeasurable. “Unscientific” came to mind because a fundamental principle in my field (psych) is that even subjective constructs such as quality can be measured to the extent that there is some shared experience between people and across time. Extraversion is a parallel example: there is no direct way to measure it, but the field has come up with clever, reliable, and valid way of measuring the level of extraversion of a given person. I think we can apply similar logic to measuring the quality of a piece of scholarship.

A central feature of measuring something subjective is its some degree of consensus. When 9 out of 10 raters say that Person A is high in extraversion, and only 2 out of 10 say that Person B is high in extraversion, and they do so consistently over time, then that is evidence that Person A’s extraversion is higher than Person B’s. Similarly, when lots of people cite Paper A, and not many cite Paper B (and they’re otherwise similar in terms of field, publication year, etc) then that can be taken as evidence that Paper A is having more influence than Paper B.

I must not have been clear on my own experience: my point was that there are exceptions, but in general I think my best work is cited more than my other work. So, correlation > 0 but < 1. Clearly, citation count is not ONLY caused by quality – outlet, surprisingness, press response, and many other factors probably contribute to citations – but it seems self evident to me that "perceived quality by other people in the field" is one driving factor behind citations. We have lots of reasons for citing other scholars' works in our work, but one reason is that we think their work was done well enough to be useful. I can't believe I'm an outlier on this point.

Chris: your point is a good one. There is no one (or may just no) relevant ordering of departments. To me, your point is all about how the data will be used. One use would be for departments to be aware of their own trends on a number of measures across time. That strikes me as useful information to have at hand (as in the example questions in my post above). Realistically, given the range of metrics under consideration, most departments will improve on some across time and decline in others. What to make of that? None of this will be interpretable without detailed insight into what is happening in the departments – which will continue to be the hardest task for deans / provosts. But I do believe that quality data (if possible) will help leadership ask the right questions.

[as always, the opinions I post here do not necessarily reflect those of my lab or department]

I agree that having proper comparators is a necessary part of this framework, and may, in the end, carry the most weight.

Hi Elliot – In response to my question you wrote:

Actually, the data on averages at comparable departments and time-trends is part of what we’ve been getting from AA for $100K a year. So let me ask how it would be used in this sort of decision, by modifying the question:

I think it’s great that economics has now come around to the conclusion – using rigorous rational optimization models – that quantifiable data is not important for many tough decisions, and can often be harmful. It was psychologists, with their empirical research on cognitive biases, that helped create that skepticism. We even gave you guys 1/2 of a scarce Nobel as thanks. So I’m hoping that there’s an answer to this question that incorporates at least something of what our two fields have learned in the past 25 years.

If not, lets just cancel the AA contract and use their money and all this wasted time to hire another professor. Heads it’s a psychologist, tails it’s an economist. You in?

Ah, I assumed your original question was tongue in cheek! I actually think that information is quite useful and would want to know it if I were in those depts. But no decision would or could be made on the basis of those data alone.

True, AA has data, but it doesn’t necessarily capture everything we’re interested in. We can get better data, at least related to ourselves.

I have a longer answer but we should talk in person. Anyone interested in this metrics discussion should come to the Senate office hours on Thursday morning to talk about it!

Hi Elliot, let me try asking a different question. Your university has enough money to pay for either:

a) One Executive Vice Provost of Academic Operations, a committee to advise him on faculty hiring, and AA data on publications and citations. Let’s call it $500K a year.

b) One new economics professor, one psychology professor, and some modest startup for the psychologist.

Which would be better for the university’s mission?

UOM, obviously the answer is:

c) Cancel AA, pay a psychology professor a small fraction of the price to do it herself, and spend the rest on a philosopher of science who can explain construct validity to the administration.

More earnestly, I wish you would stop framing the issue in terms of zero-sum decisions like this. We as a university need to make hard decisions all the time in a resource-scarce environment. These decisions are going to be made one way or another. Many people will be displeased with the outcomes of the decisions regardless of which way they go. Right now, we have an opportunity to shape a small piece of the information that goes into those complex decisions. I see this as a tremendous opportunity to improve the process. I am sure I am not the only one who wants to improve things here. So, for those interested, please come to Senate office hours Thursday and/or contact me and/or your deans with constructive input!

A central administration that cannot hire a visiting conductor of baroque music without fucking it up should not be allowed to run an Institutional Hiring Plan for the entire faculty.

mine’s smaller …

“Making the criteria for quality explicit and transparent can reduce some of the biases that come along with summary evaluations of departments.”

This sounds exactly like the kind of thing that creates or exposes new biases…

There are quite a few other metrics being proposed out there – maybe we should consider them? http://www.academiaobscura.com/alternatesciencemetrics/