UO Board of Trustees Chair Chuck Lillis is a former marketing professor and dean, and the only regular UO trustee with a PhD. (Academic publications and citations here, ERISA lawsuit settlements here.) He started off a Board meeting a few years back with a brief rant about deadwood tenured faculty. Newly appointed President Mike Schill responded with a vigorous defense of UO’s faculty, and since then Lillis and the rest of the board has switched to saluting Schill for his very successful efforts to maintain UO as a viable research university, with all the respect to the faculty that this requires – such as tenure.

But was Lillis right? A soon to be published paper looks at the publishing patterns of pre- and post-tenure faculty at top Economics departments (top 50 as of 1995, which sadly excludes UO Econ) and concludes he was. Here’s the report from InsideHigherEd:

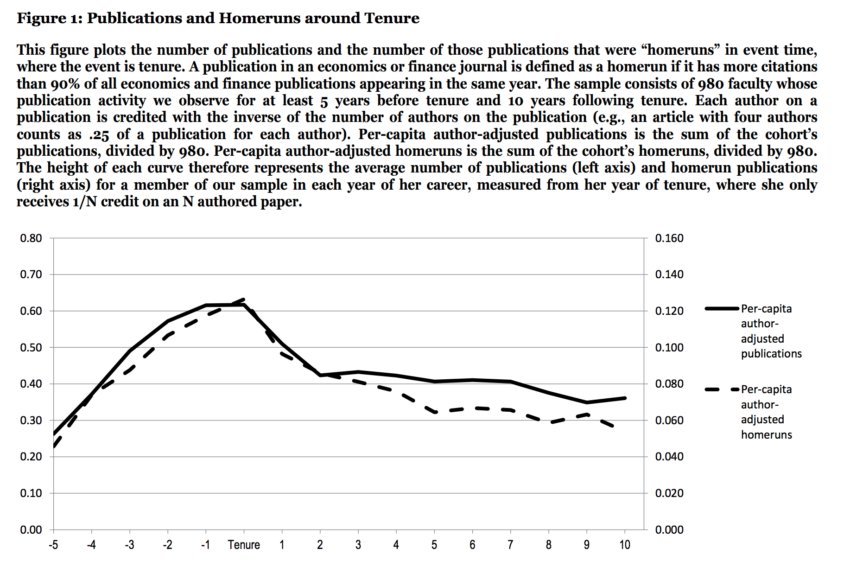

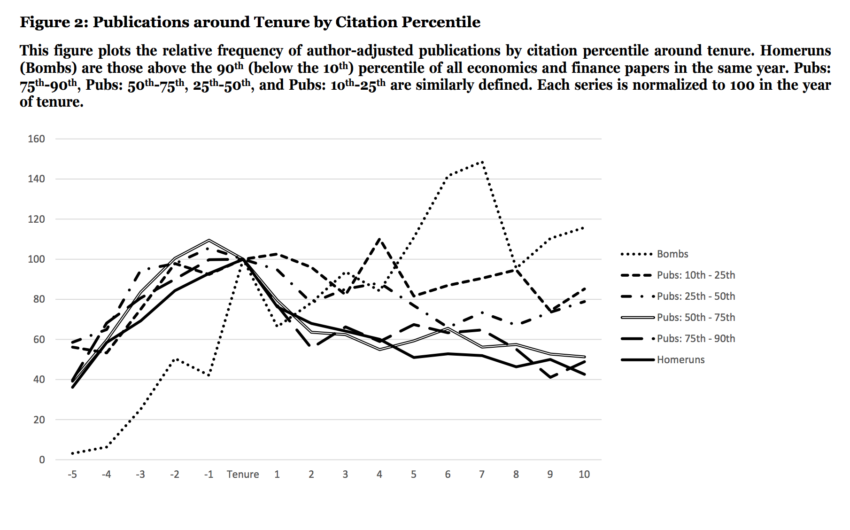

Malaise, slump, deadwood — there are lots of words for what supposedly happens to professors’ research outputs after tenure. A forthcoming study in the Journal of Economic Perspectives doesn’t use any of those terms and explicitly says it must not be read as an “indictment” of tenure. But it suggests that research quality and quantity decline in the decade after tenure, at least in economics.

The authors of the paper — Jonathan Brogaard, an assistant professor of finance at the University of Washington at Seattle; Joseph Engelberg, professor of finance and accounting the University of California, San Diego; and Edward Van Wesep, associate professor of finance at the University of Colorado at Boulder — started with a question: “Do academics respond to receiving tenure by being more likely to attempt ground-breaking ‘homerun’ research and in this way ‘swinging for the fences?’”

After all, they wrote, “the incentives provided by the threat of termination are perhaps the starkest incentives faced by most employees, and tenure removes those incentives.” (The question is sure to annoy academic freedom watchdogs. In the authors’ defense, they do cite the benefits of tenure, including job stability’s potential to encourage risk taking.) …

The paper is here. The gist:

The paper of course includes all the expected qualifications against using these figures or the statistical analysis to conclude that tenure is a bad thing.

FWIW Chuck, my own publishing and citation record is here. I was tenured in 2001. Of my top 5 publications in terms of citations, 3 were published after tenure.

In my own case, the most highly cited work as faculty member came after tenure.

Actually, the graph shows that the average output is about the same before and aftwr tenure. A lag ar first, a jump before tenure, back to the average after.

Even though asst profs, in my field at least, get sumptuous research startup money, light teaching and service — all designed to foster that bump.

I would say Schill was right, Lillis didn’t know what he was talking about.

He by the way the guy who bugged out of academia for the world of easy money.

Distracting you with a shiny piece of deadwood while he’s busy pillaging the University.

The summary of the paper appears to leave out other important contributions to the academic institution that are typically sacrificed in the pursuit of tenure, including teaching, advising, departmental/institutional/disciplinary service. In my anecdotal experience, those latter things tend to increase, on average, once a professor gains tenure.

There may also be a relationship between publishing and institutional support, namely startup funds versus ongoing institutional support.

I’ve seen other research which seems to indicate that productivity peaks about ten years after one begins one’s career, regardless of when that career started (i.e., biological age) or one’s career trajectory. This would coincide with when someone typically gets tenure. So it’s another confounding variable.

You got a citation for us?

Dean K Simonton at UC Davis has done work on this, for example here. It’s been awhile since I’ve looked at this, so no promises about whether I’m remembering his conclusions accurately.

speaking from the position of being actual Deadwood (my academic colleagues have claimed so) – my personal opinion is that I may or may not be deadwood. However, in my experience, deadwood is clearly defined by the number of papers published per year in the Journal of Incremental Knowledge – if you are below that threshold

for 2-3 years in a row – you are judged as deadwood – your other academic accomplishments and contributions do not seem to matter.

In my personal case I have consciously decided about 5 years ago to transition out of the Incremental Knowledge submissions and transition into other kinds of media to communication of thoughts, ideas, data and results, but there is no peer-recognized value of scholarship in these other directions. While I personally don’t care about this, the departmental rather tunnel visioned metrics for

what constitutes “academic success” does need to evolve …

I think the big “news” to parse here is that productivity and success is being evaluated based on peer reviewed publications. Seems to be a university professor also has obligations regarding service, developing skills to TEACH, engaging students and such. THAT’s what they are paid for by tuition. Not just the CV, right? SO I tend to lean toward Dog . . .

I think the “deadwood” is the outdated publish or perish paradigm.

What strikes me as somewhat strange is the consistent failure on

the part of “what success is being evaluated on” is that we are

a State University (yes less so now, than in the past). I have had jobs

at both public and private Universities and I will admit that

I didn’t care much about teaching and “other stuff” when I was at

a private university. I have always felt that faculty at Public

Universities have a different set of obligations – but I think this is

a minority opinion …

Is this that tenure is bad, or the threat of being denied tenure spurred a temporary productivity burst? That sort of spurt is sustainable. Or for those who can sustain it, they get outside offers and move on. We can’t expect people to work 80 hours a week and give up their weekends forever can we?

It was just Lillis throwing another hissy fit because there is any limit to his power, same as with his grudge against the HECC. He doesn’t really care whether you are deadwood, he just doesn’t like the idea that he can’t wave his hand and make you disappear.

oh please, Chuck, wave the hand, wave the damn hand

Since tenure decisions are made, at least in part, on the basis of research productivity at the time of the tenure decision, one would expect, ceteris paribus, for those who received tenure to have been unusually productive at the time the decision was made relative to the rest of their career, even baring any incentive effect.

See the “Low birth-weight paradox” and “Survivorship bias” for more.