Elevator version: The Oregon Supreme Court tells the Oregon Board of Bar Examiners that they must add a new at-home bar exam for October, and give “diploma privilege” to all Oregon and most other law school 2020 grads, allowing them the right to practice law in Oregon if they can find…

Posts tagged as “grade inflation”

Info on former UO CAS Assoc Dean Ian McNeely’s 2009 effort to bring grade inflation (most present in non-STEM fields) under control, which failed after massive faculty opposition and Johnson Hall indifference, is here. If the argument below is correct, it would have led to a large shift of students…

9/27/2017 with 10/4 update:

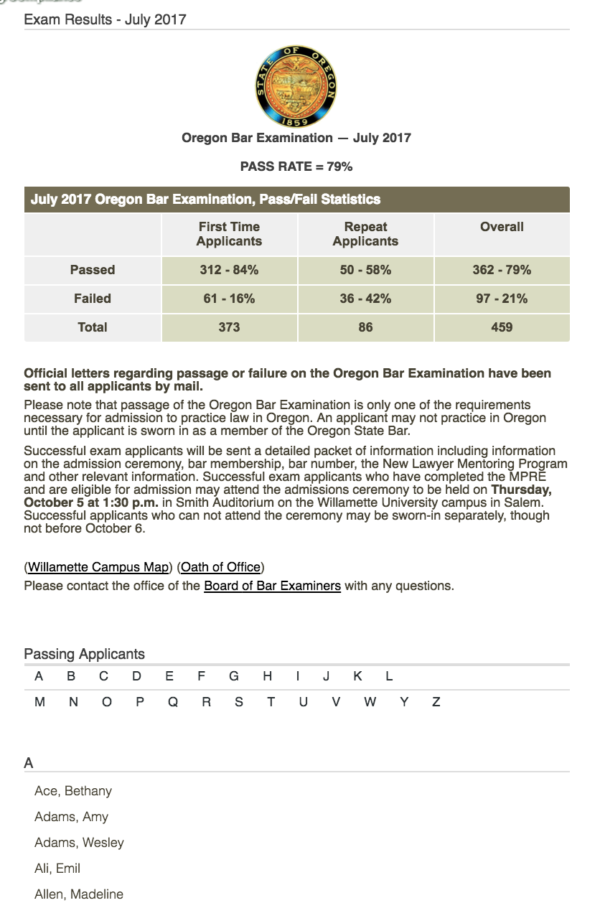

Normally about 260 people pass the July Oregon Bar exam. This spring the Oregon Supreme Court dumbed down the pass score and made some other changes, and 360 people passed. Obviously this is good news for the 100 students who otherwise wouldn’t be licensed to practice law, and good news for the Oregon Bar, which collects an annual $470 from each. It’s bad news for those 260 students who would have passed the older, harder exam, and who now have to try and find a job in an even more flooded job market.

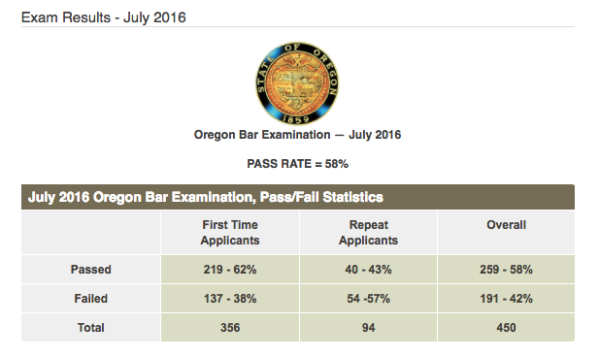

Oregon’s pass rate for the July exam, (all takers, not just UO students) has jumped from 58% last year to 79% this year. That’s a 21 percentage point increase or a (79-58)/58=36% increase in the success odds, in one year. In July 2016 the average pass rate for all US takers was 62%, compared to 58% for Oregon. So we were a little low, but not by much.

In July 2016, only Nebraska had a higher percentage of takers (82%) passing than Oregon’s 2017 new rate of 79%. (Kansas and Missouri were tied at 79%, Oregon’s new rate). See http://www.ncbex.org/pdfviewer/?file=%2Fdmsdocument%2F205 So, with one decision made without adequate prior public notice or discussion, and apparently with no discussion in the Oregon Supreme Court, Oregon has gone from being middle of the road to being among the four easiest states in which to get a license to practice law.

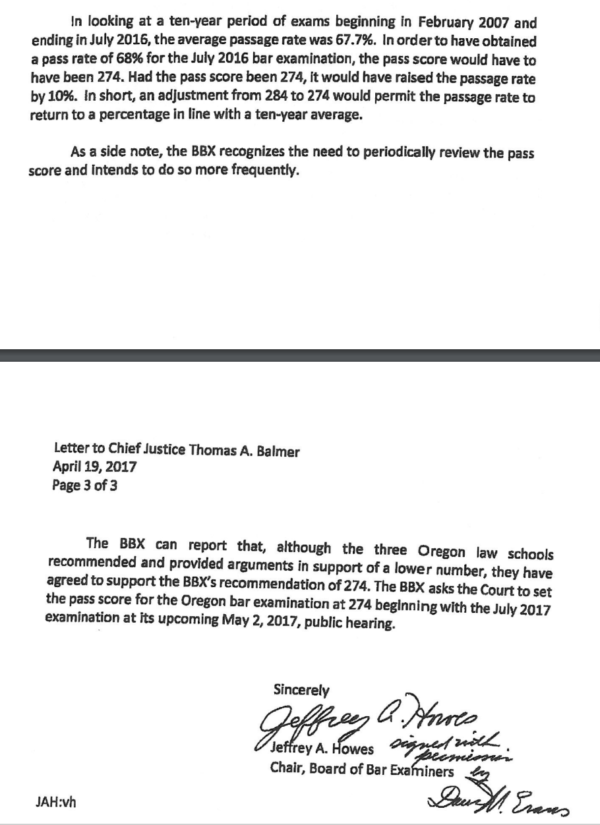

This is not what the Oregon Board of Bar Examiners intended. According to internal documents obtained with a public records request, the BBX believed these changes would increase the pass rate to about 68%. They explicitly rejected a proposal from the three deans of Oregon’s law schools for an even lower cut-score, apparently because they thought that would produce a pass rate of 78%, which they thought was too high. I wonder if the deans will now argue for raising the cut-score and lowering the pass rate?

(From the April 19 letter from BBX chair Jeffrey Howes to Oregon Chief SC Justice Thomas Balmer, at https://uomatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Official-letters-to-Court-BBX-PubRcrdsReq-Aug-17.pdf)

In short Oregon’s new test, with the new lower cut-score, is much easier to pass than the old one, and much easier than the BBX led the Supreme Court to believe. It has given Oregon what is almost the highest pass rate in the country.

It’s true that the new exam will also make it easier for Oregon law students to move to other states, assuming their score was high enough to have passed those state’s cut-rate. But why is Oregon subsidizing the tuition of out-of-state students who will take out-of state legal jobs – if they can even find them?

For comparison, last July:

Michael Tobin has a brief report about this in the Daily Emerald, here.

10/4/2017 NOTE: I’ve now received two letters from the Oregon Bar, arguing that they did not break the public meetings law, while also promising that they will now post meeting notices on the bar’s website. As you can see from their October posting, they’re still trying to figure this transparency thing out:

…

I’ve got some more public records requests into them and the Oregon Supreme Court (which has updated its website and fixed some of its public records procedures in response to my previous questions to them) and I will post what I find out.

Posted 9/27/2017 and earlier:

Will Campbell has an excellent data driven story with the history of UO’s failed efforts to fight grade inflation in the Emerald here: … In 2009, when [CAS Associate Dean Ian McNeely] became chair of the Undergraduate Council, the university-wide body that oversees undergraduate education, he became familiar with grade inflation.…

From today’s Harvard Crimson: “I can answer the question, if you want me to.” (Dean) Harris said. “The median grade in Harvard College is indeed an A-. The most frequently awarded grade in Harvard College is actually a straight A.” From UO Matters story, “VPAA Doug Blandy pulls off daring…

8/23/2011: Apparently the average grade in upper level courses in UO’s College of Education is now 4.04. This generic problem at Ed schools is described and criticized in this paper (data shown is from Indiana): This paper documents a startling difference in the grading standards between education departments and other academic departments…